US tightens control of Venezuelan oil, sparks debate in Congress

Washington, Jan 8 : The Trump administration is moving to tighten US control over Venezuela's oil exports through sanctions enforcement, a naval presence, and US-managed sales, according to top administration officials, even as lawmakers pressed the White House for clearer objectives and legal justification.

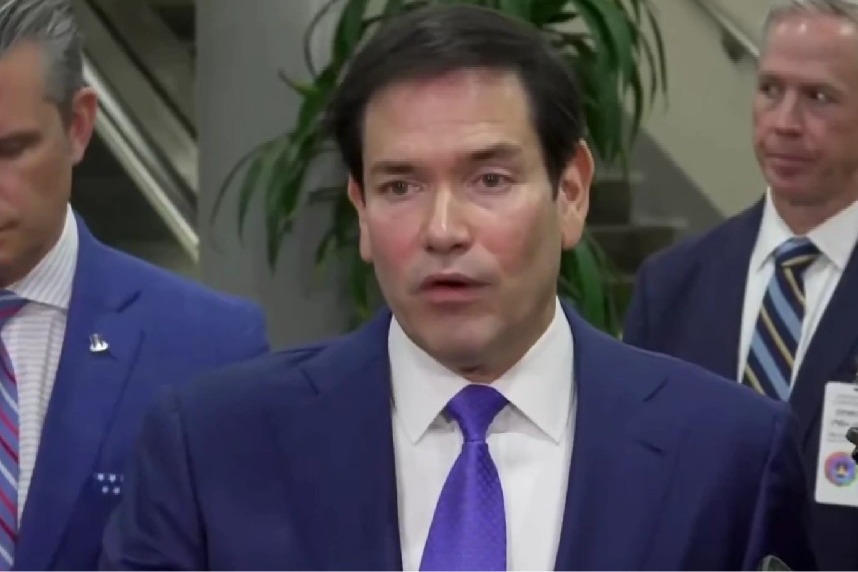

Following a closed-door meeting with lawmakers, Secretary of State Marco Rubio told reporters that Venezuela cannot export oil without US approval, describing Washington's leverage over the country's energy sector as central to stabilisation after the removal of its President, Nicolas Maduro.

"We have an oil embargo on Venezuela. For them to do any kind of commerce, they need our permission," he said.

Rubio said the United States is enforcing that embargo through a continued naval presence in the Caribbean and by authorising only selected, US-supervised oil movements. The approach, he said, is intended to prevent corruption, block sanctions evasion, and ensure oil revenue is not diverted to criminal networks.

That posture was reinforced a day earlier by President Donald Trump in a social media post announcing that Venezuela's interim authorities would turn over between 30 million and 50 million barrels of sanctioned oil to the United States.

Trump said the oil would be sold at market prices and that proceeds would be controlled by him to benefit both Venezuelans and Americans.

The Energy Department, in a fact sheet released on Wednesday, said the United States plans to oversee the sale of those barrels, with proceeds routed through US-controlled accounts. Officials said the arrangement allows limited oil flows while keeping financial control firmly in Washington's hands.

For India, one of the world's largest crude importers, the developments are closely watched. Venezuela holds the world's largest proven oil reserves and was once a key supplier of heavy crude to Indian refiners before US sanctions halted imports in 2019. Any re-entry of Venezuelan oil into global markets -- even under US supervision -- has implications for supply, pricing, and competition among major buyers.

Republican lawmakers praised the strategy as decisive. Senator John Cornyn said the operation and oil controls sent a clear message that the United States will enforce sanctions and hold leaders accountable. Senator John Barrasso described the Maduro operation as one of the boldest law-enforcement actions in decades and argued that tighter control of Venezuelan oil weakens what he called a sanctions-defying network involving China, Russia and Iran.

Democrats raised alarms about shifting rationales and the absence of prior congressional authorisation. In prepared remarks after a classified House briefing, Representative Gregory Meeks, the top Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said the administration's objectives appeared to have moved "from drugs to regime change to controlling a country and its oil."

"The administration owes Congress and the American people a clear and honest explanation of its actual objectives in Venezuela," Meeks said.

Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin echoed those concerns on the Senate floor, saying lawmakers left briefings with "more questions than answers", particularly about costs, duration and the risk of a prolonged US role tied to oil infrastructure.

Another flashpoint is whether US actions amount to de facto control of Venezuela's energy sector.

Indian American Congressman Raja Krishnamoorthi announced plans to introduce legislation barring any use of federal funds to occupy or administer Venezuela, including its oil industry, without explicit congressional approval.

The Trump administration rejected all claims of occupation.

Rubio told lawmakers that leverage over oil is a temporary stabilisation tool, not a permanent takeover.

The Energy Department fact sheet said that Venezuela's infrastructure is badly degraded and will require years of work and foreign expertise to restore.

Following a closed-door meeting with lawmakers, Secretary of State Marco Rubio told reporters that Venezuela cannot export oil without US approval, describing Washington's leverage over the country's energy sector as central to stabilisation after the removal of its President, Nicolas Maduro.

"We have an oil embargo on Venezuela. For them to do any kind of commerce, they need our permission," he said.

Rubio said the United States is enforcing that embargo through a continued naval presence in the Caribbean and by authorising only selected, US-supervised oil movements. The approach, he said, is intended to prevent corruption, block sanctions evasion, and ensure oil revenue is not diverted to criminal networks.

That posture was reinforced a day earlier by President Donald Trump in a social media post announcing that Venezuela's interim authorities would turn over between 30 million and 50 million barrels of sanctioned oil to the United States.

Trump said the oil would be sold at market prices and that proceeds would be controlled by him to benefit both Venezuelans and Americans.

The Energy Department, in a fact sheet released on Wednesday, said the United States plans to oversee the sale of those barrels, with proceeds routed through US-controlled accounts. Officials said the arrangement allows limited oil flows while keeping financial control firmly in Washington's hands.

For India, one of the world's largest crude importers, the developments are closely watched. Venezuela holds the world's largest proven oil reserves and was once a key supplier of heavy crude to Indian refiners before US sanctions halted imports in 2019. Any re-entry of Venezuelan oil into global markets -- even under US supervision -- has implications for supply, pricing, and competition among major buyers.

Republican lawmakers praised the strategy as decisive. Senator John Cornyn said the operation and oil controls sent a clear message that the United States will enforce sanctions and hold leaders accountable. Senator John Barrasso described the Maduro operation as one of the boldest law-enforcement actions in decades and argued that tighter control of Venezuelan oil weakens what he called a sanctions-defying network involving China, Russia and Iran.

Democrats raised alarms about shifting rationales and the absence of prior congressional authorisation. In prepared remarks after a classified House briefing, Representative Gregory Meeks, the top Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said the administration's objectives appeared to have moved "from drugs to regime change to controlling a country and its oil."

"The administration owes Congress and the American people a clear and honest explanation of its actual objectives in Venezuela," Meeks said.

Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin echoed those concerns on the Senate floor, saying lawmakers left briefings with "more questions than answers", particularly about costs, duration and the risk of a prolonged US role tied to oil infrastructure.

Another flashpoint is whether US actions amount to de facto control of Venezuela's energy sector.

Indian American Congressman Raja Krishnamoorthi announced plans to introduce legislation barring any use of federal funds to occupy or administer Venezuela, including its oil industry, without explicit congressional approval.

The Trump administration rejected all claims of occupation.

Rubio told lawmakers that leverage over oil is a temporary stabilisation tool, not a permanent takeover.

The Energy Department fact sheet said that Venezuela's infrastructure is badly degraded and will require years of work and foreign expertise to restore.